A fundamental principle of economics is that any policy should be judged not by its intentions but by its outcomes. In education, outcomes are measured by whether a child is genuinely learning, able to cope with the school environment, and acquiring skills that prepare them for a competitive future.

The Supreme Court recently reminded us that under the Right to Education (RTE) Act, 25% of seats in private schools are reserved for children from disadvantaged backgrounds. While the law’s intent is noble—education can indeed be a transformative tool—the reality of implementation requires scrutiny. Simply providing seats does not ensure that children benefit in meaningful ways.

The Cost of Learning

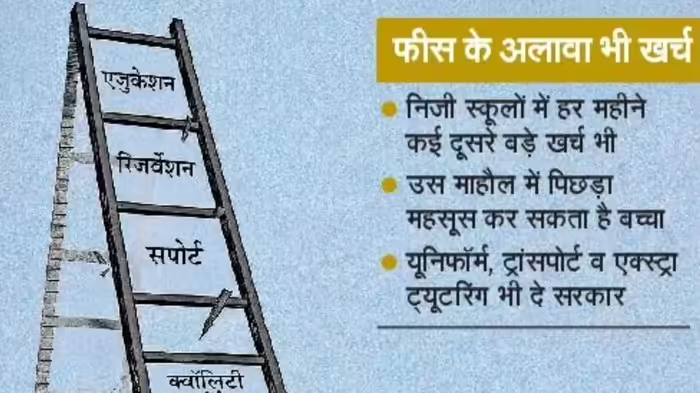

The challenge lies in our tendency to reduce education to a debate over “seats” or “fees.” Free tuition does not equal free education. Every family bears a real cost: money, time, mental stress, and risk. Even if tuition is waived, families often incur additional monthly expenses of ₹3,000–₹5,000 for books, uniforms, stationery, projects, and transport. For a daily-wage worker, this can account for 40–50% of monthly income.

Hidden Costs

Beyond money, time and procedural complexity create a hidden burden. Document verification, navigating portals, and office visits consume time that could otherwise earn a livelihood. Economists call this “opportunity cost”—every day spent fulfilling formalities translates to lost income for families. Policies rarely account for these hidden costs.

Psychological Barriers

Schools are not just academic centers; they are micro-societies. Children face subtle competitions over tiffin, clothing, branded shoes, mobile phones, language skills, birthday parties, and trips. For a disadvantaged child, the awareness of being different can diminish learning productivity. They may attend classes physically but remain mentally excluded from the learning process.

Environmental Gap

The disparity between public and modern private schools is evident. A child admitted under a 25% quota in a private school may not experience the same technological, social, and cultural environment at home, limiting the policy’s effectiveness.

Low-Return Investment

Education, like production in a factory, requires more than a seat (machine). Adequate inputs—safe housing, nutrition, a conducive study environment, and extra support—are essential. Without them, the educational output is limited, making the policy a “low-return investment.”

Paths to Solutions

- The government must provide more than fee reimbursement, including support packages for uniforms, transport, and extra tutoring.

- Schools must cultivate an “inclusion culture.” Pilot projects in some states, pairing disadvantaged students with peers and appointing inclusion coordinators, have improved learning outcomes by up to 30%.

- Most importantly, public schools must be strengthened. Until they match private schools in quality, efforts to provide justice through quotas will remain fragmented. The focus should not be on which school a child attends, but on what they are learning.

Discover more from SD NEWS agency

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.