The Supreme Court has recently reiterated a crucial reminder: under the Right to Education (RTE) Act, 25 per cent of seats in private schools are reserved for children from economically weaker sections. While this observation reinforces the legal mandate, it also seeks to awaken our collective social conscience.

The intent of the law is unquestionably noble. Education is perhaps the most reliable tool for transforming lives. However, a fundamental principle of economics tells us that public policies must be judged not by their intentions, but by their outcomes.

In the context of education, outcomes mean more than mere enrollment. The real questions are: Is the child actually learning? Is the child able to continue in school without dropping out? Are these children acquiring skills that prepare them for a competitive future?

Unfortunately, the current implementation of RTE in private schools reveals at least six serious challenges.

1. The True Cost of Learning

Public debate around RTE often stops at “free seats” or “fee waivers.” The assumption is that once tuition fees are waived, education becomes free. This is a misconception. Learning carries a total cost—financial, temporal, psychological, and social.

Economists describe this as the total cost of education, which goes far beyond school fees.

2. Expenses Outside the Fee Structure

Even after securing admission under the RTE quota, poor families face multiple direct expenses: textbooks, uniforms, stationery, project materials, and transportation. In many elite private schools, expenses such as canteen food, special sports kits, or extracurricular fees are effectively compulsory.

When calculated together, these costs often amount to ₹3,000–₹5,000 per month. For a daily-wage worker or agricultural laborer, this can consume 40–50 per cent of the household’s monthly income.

3. Hidden Costs and Opportunity Loss

Beyond money, there is the cost of time. Document verification, portal-related technical hurdles, and repeated visits to school offices impose a significant burden. For low-income families, this time comes directly at the cost of livelihood.

Economists call this opportunity cost—a day spent completing school formalities is a day of lost wages. Policymakers rarely account for this invisible yet substantial burden.

4. The Psychological Barrier

Schools are not merely academic institutions; they are micro-societies. Children compete over lunchboxes, clothing brands, English accents, smartphones, birthday parties, and school trips. Participation in these social rituals often carries a high economic and emotional cost.

When a child repeatedly feels “different” or inferior, learning productivity declines. This psychological wall keeps the child physically present in the classroom but mentally disengaged from learning.

5. Environmental Inequality

This is where the gap between municipal schools and elite private schools becomes stark. A child studying in a modern private school is surrounded by technology, internet access, and exposure. Can a child admitted under the RTE quota return home to the same environment?

If the household lacks stable electricity, internet access, or parents who can support academic work, the child inevitably falls behind—despite sitting in the same classroom.

6. A Low-Return Policy Investment

Learning is a production process. Just as a factory needs more than machines to produce quality goods, education requires nutrition, a safe home, a supportive study environment, and remedial support.

Without these inputs, educational outcomes remain weak. In such conditions, the RTE policy risks becoming a low-return social investment.

The Way Forward

First, the government must go beyond reimbursing tuition fees. A comprehensive support package—covering uniforms, transport, learning materials, and supplementary tutoring—must be funded for RTE students.

Second, schools must actively foster an inclusive culture. Evidence from pilot projects in some states shows that initiatives such as buddy systems (pairing children from different socio-economic backgrounds) and dedicated inclusion coordinators have improved learning outcomes by up to 30 per cent.

Third—and most importantly—improving the quality of government schools remains the first-best solution. Until public schools match private institutions in quality, RTE will continue to deliver fragmented justice.

The ultimate goal should not be which school a child attends, but what the child actually learns.

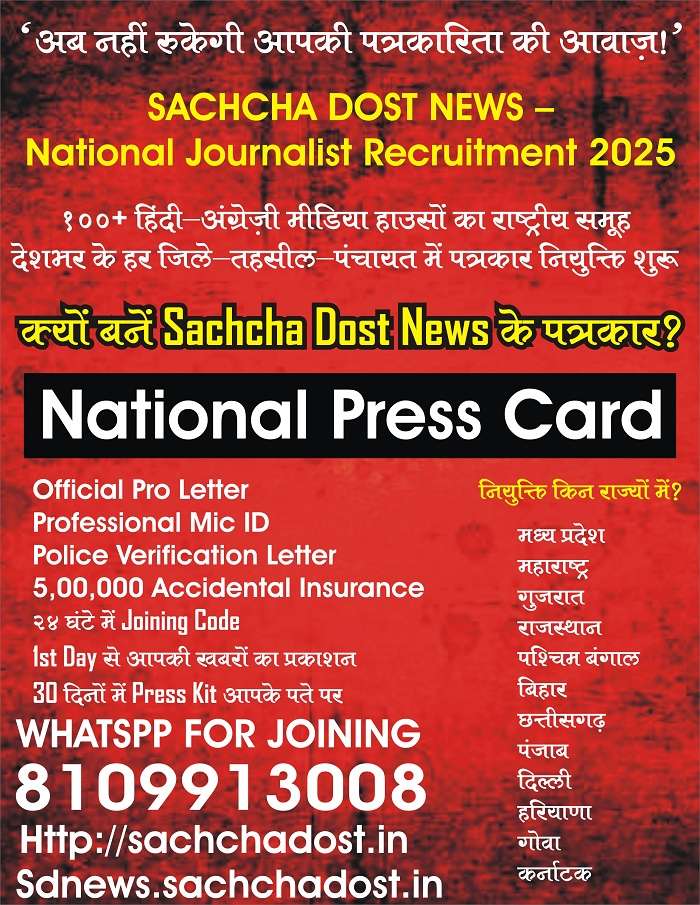

Discover more from SD NEWS agency

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.